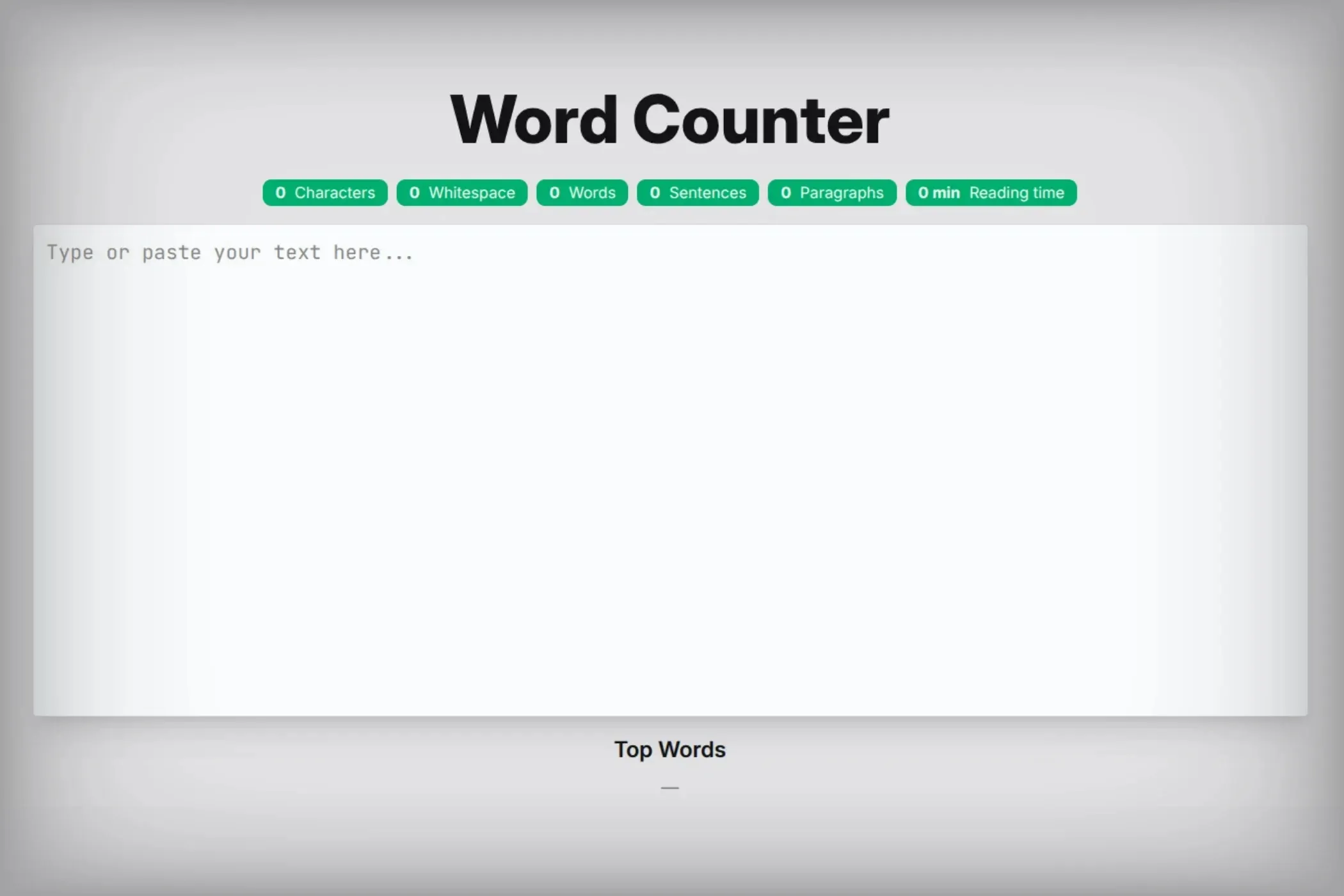

Made in the Browser: Word Counter

How the Vayce Word Counter reads your text locally, from graphemes and emojis to sentences and reading time

Thu Oct 23 2025 • 8 min read

Every writer uses a word counter but few know what it’s really doing.

You paste a draft into a box, numbers appear instantly, and you move on. But inside that moment, your browser is performing dozens of small linguistic calculations: segmenting characters, interpreting punctuation, normalizing spaces, and guessing how long it might take to read what you wrote.

This article peels back that layer and shows how the Vayce Word Counter works and, by extension, how most modern word counters operate. It’s not about counting spaces. It’s about teaching the browser to read text.

Characters, Graphemes, and Why They’re Different

Computers think in code points - not what humans see as letters.

The word “café” contains an accented “é,” which is actually two code points (e + ´) in many encodings.

Emojis can be even more complex: 👨👩👧👦 looks like one character, but it’s seven code points joined by invisible markers.

The browser has a built-in tool for this: Intl.Segmenter, which can detect visible characters, or grapheme clusters.

The Intl object is short for Internationalization. It’s a JavaScript namespace that contains language-aware features. Things like date formatting, number localization, and, in this case, text segmentation.

A grapheme cluster is the smallest visible unit of text. It’s what humans perceive as a single character, even if it’s made of multiple code points under the hood (like “é” or family emojis)

function countGraphemes(text) {

if (typeof Intl !== 'undefined' && Intl.Segmenter) {

const seg = new Intl.Segmenter(undefined, { granularity: 'grapheme' });

return [...seg.segment(text)].length;

}

return Array.from(text).length; // fallback

}This simple function ensures every emoji, accent, and symbol is counted exactly once.

You can test it yourself:

countGraphemes('👨👩👧👦'); // 1

countGraphemes('café'); // 4It’s one of those APIs that make you appreciate how much invisible work the browser can already do for you.

What Counts as a Word?

Once you can count characters reliably, words are the next puzzle and they’re not as simple as “anything between spaces.”

Take this line:

Dr. Smith's email—[email protected]—arrived at 8:00 a.m.That single sentence already mixes abbreviations, punctuation, numbers, and special tokens. Let’s unpack how a browser can handle all that gracefully.

Start simple

At first you might try this:

text.split(' ')That works for short notes but collapses instantly in real text. Extra spaces, smart quotes, and non‑Latin scripts all break it.

So instead of spaces, we start with Unicode letter and number classes (\p{L} and \p{N}) which cover every alphabet and numeral system.

const CORE_WORD = String.raw`[\p{L}\p{N}]+(?:[-'’\u2019][\p{L}\p{N}]+)*`;

const rx = new RegExp(CORE_WORD, 'gu');

text.match(rx);Now don’t, co‑op, and even Greek or Cyrillic words count correctly. But we’re still missing a few important kinds of tokens.

Handle special cases

Writers don’t just type words. They include emails, URLs, acronyms, and times. All of these can break simple tokenizers. The solution is to treat them as valid word alternatives, not as noise.

Here’s what that means in code:

const EMAIL = String.raw`[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,}`; // [email protected]

const URL = String.raw`(?:https?:\/\/|www\.)\S+`; // https://vayce.app

const INITIALISM = String.raw`(?:\p{L}\.){2,}`; // e.g.

const NUMBER_SEQ = String.raw`\d+(?:[,:.]\d+)+`; // 8:30, 3.14, 1,000.50Each of these patterns catches a class of tokens that real text contains. By keeping them separate, you stay flexible. You can count or ignore them later.

Put it together

Combine everything into one regex. Order matters: specific tokens first, then the generic word rule.

const TOKEN = new RegExp(`${EMAIL}|${URL}|${INITIALISM}|${NUMBER_SEQ}|${CORE_WORD}`, 'gu');

function wordMatches(text) {

return text.match(TOKEN) || [];

}

function countWords(text) {

const tokens = wordMatches(text);

// Optionally skip emails/URLs from the word count

return tokens.filter(t => !/^(?:https?:\/\/|www\.|[\w.+-]+@)/i.test(t)).length;

}This approach is fast, Unicode‑aware, and resilient. It doesn’t alter the text. It simply understands more of it.

Sentences and Abbreviations

Sentence detection is where text analysis gets messy. Dr., U.S., 3.14, and a.m. all look like sentences to a simple splitter.

Let’s build a smarter one.

Modern browsers as we said already ship with Intl.Segmenter, which understands sentence boundaries for many languages:

function sentencesIntl(text) {

const seg = new Intl.Segmenter(undefined, { granularity: 'sentence' });

return [...seg.segment(text)]

.map(s => s.segment.trim())

.filter(s => /\p{L}|\p{N}/u.test(s));

}If available, that’s all you need. It handles punctuation, quotes, and locales correctly. But for broader support, we add a fallback.

Protect what’s not a sentence boundary

Before splitting, we replace periods in special patterns (like emails or abbreviations) with a temporary marker so they don’t trigger false splits.

const MARK = '¶';

const restore = t => t.replace(new RegExp(MARK, 'g'), '.');

function protectEmailsAndUrls(text) {

text = text.replace(/[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,}/g, m => m.replace(/[.@:]/g, MARK));

return text.replace(/(?:https?:\/\/|www\.)\S+/g, m => m.replace(/[.:\/]/g, MARK));

}

function protectNumbers(text) {

return text.replace(/\d(?:[.,:]\d)+/g, m => m.replace(/[.,:]/g, MARK));

}

function protectInitials(text) {

return text

.replace(/(?:\p{L}\.){2,}/gu, m => m.replace(/\./g, MARK)) // U.S.A.

.replace(/\b(\p{L})\.(?=\s|\p{Lu}\b)/gu, (_, a) => a + MARK); // J. K.

}

function protectAbbreviations(text) {

const abbrs = ['Mr','Mrs','Ms','Dr','Prof','Sr','Jr','St','Mt','U.S','U.K','e.g','i.e','etc','vs','Ltd','Inc'];

let out = text;

for (const a of abbrs) {

const rx = new RegExp('\\b' + a.replace('.', '\\.') + '\\.', 'ig');

out = out.replace(rx, m => m.replace(/\./g, MARK));

}

return out;

}Each helper removes a source of confusion (abbreviations, decimals, initials, emails) by marking their punctuation temporarily.

Split and clean up

Once protected, we can safely split by sentence punctuation and restore the text.

const SENTENCE_RX = /[^.!?…\r\n]+?(?:[.!?…]+(?:["')\]\u00BB\u201D\u2019»]*)|$)(?=\s+|\r?\n|$)/gu;

function countSentences(text) {

if (!text) return 0;

// Try Intl first

if (typeof Intl !== 'undefined' && Intl.Segmenter) {

try {

const seg = new Intl.Segmenter(undefined, { granularity: 'sentence' });

const parts = [...seg.segment(text)].map(s => s.segment.trim()).filter(s => /\p{L}|\p{N}/u.test(s));

if (parts.length) return parts.length;

} catch {}

}

const safe = protectAbbreviations(protectInitials(protectNumbers(protectEmailsAndUrls(text))));

const raw = safe.match(SENTENCE_RX) || [];

const cleaned = raw

.map(s => restore(s).trim().replace(/^[("'\[\u00AB\u201C\u2018«\s]+|[)"'\]\u00BB\u201D\u2019»\s]+$/g, ''))

.filter(s => s.length > 0 && /[^\s\p{P}]/u.test(s));

return cleaned.length;

}This fallback catches nearly everything. Abbreviations, decimals, quotes, even a final unpunctuated line.

Paragraphs and Reading Time

Paragraphs are conceptually simple text blocks separated by one or more blank lines:

function countParagraphs(text) {

const paragraphs = text.split(/\s*\n+/).map(s => s.trim()).filter(Boolean);

return paragraphs.length || (text.trim().length > 0 ? 1 : 0);

}And reading time? A small but useful metric. Most adults read around 200 words per minute.

function measureReadingTime(words, averageReadingTime = 200) {

return +(words / averageReadingTime).toFixed(2);

}This turns your word count into a meaningful real-world estimate: a 400-word article takes about two minutes to read.

Finding Common Words

Word frequency is the last layer and it’s surprisingly helpful for writers. You can detect overused words, recurring themes, or filler terms at a glance.

function wordFrequency(text, max = 10) {

const arr = wordMatches(text).map(w => w.toLowerCase());

const map = new Map();

for (const w of arr) map.set(w, (map.get(w) || 0) + 1);

return [...map.entries()].sort((a,b)=>b[1]-a[1]).slice(0,max);

}This produces a ranked list of the most frequent words. Useful for both editing and SEO. Writers can immediately see if they’re repeating adjectives or using filler too often.

Tying It All Together

Each of these small counting functions runs instantly in the browser. When you type, the app listens to each input event and recalculates everything using [useMemo](https://preactjs.com/guide/v10/hooks/#usememo) from Preact:

const stats = useMemo(() => {

const chars = countChars(text);

const charsNoSpaces = countCharsNoSpaces(text);

const words = countWords(text);

const sentences = countSentences(text);

const paragraphs = countParagraphs(text);

const readingTimeMinutes = measureReadingTime(words);

const topWords = wordFrequency(text, 10)

return {

words, chars, charsNoSpaces, sentences, paragraphs, readingTimeMinutes, topWords

};

}, [text]);useMemo is perfect here because it recomputes the statistics only when the text actually changes.

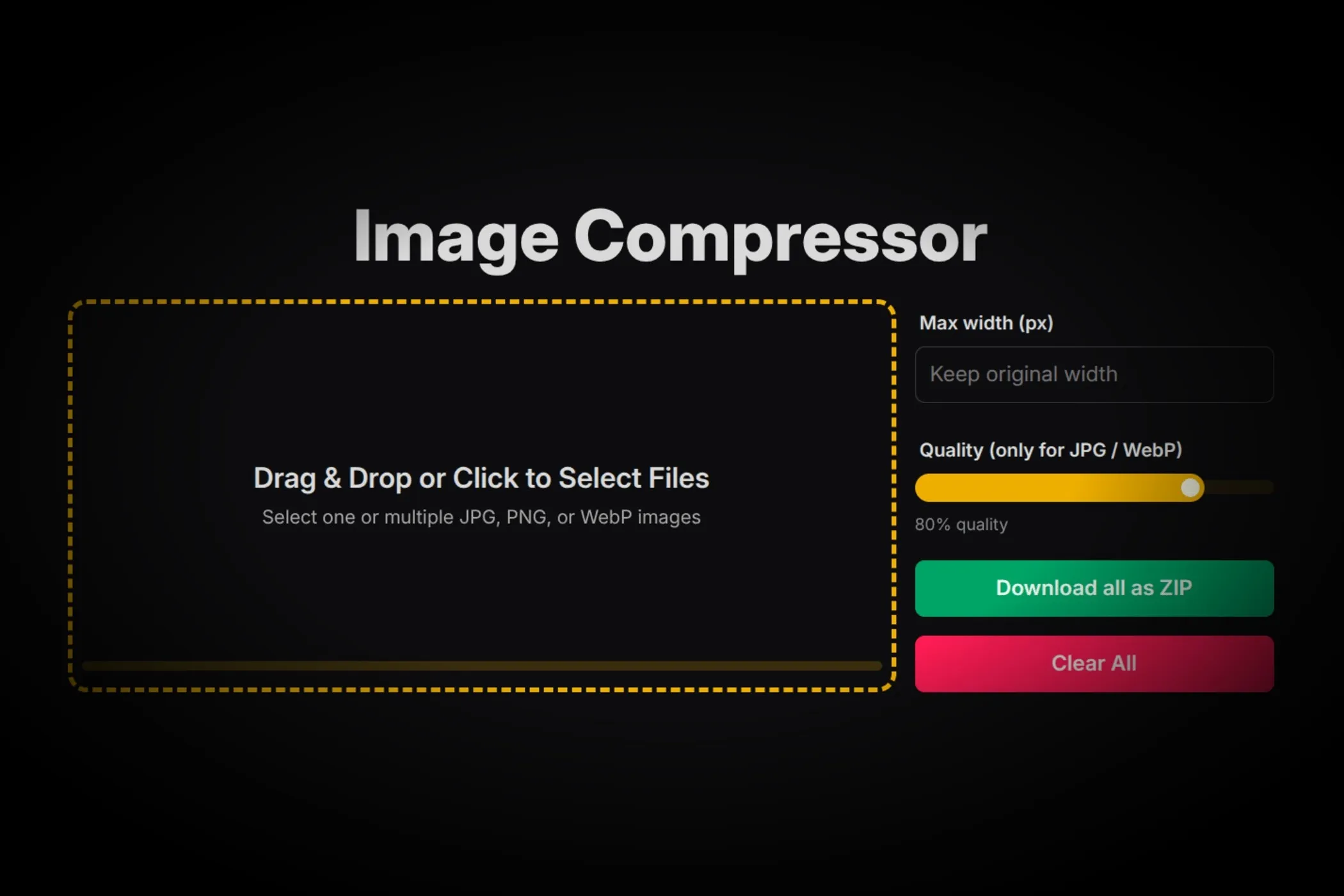

As the user types, the display updates, showing a dashboard of badges for words, characters, sentences, and paragraphs, along with the estimated reading time and top words

Everything happens instantly, in memory, with zero dependencies.

The Interface: Simple but Thoughtful

The design follows the same philosophy: clarity and feedback.

- Each badge represents a measurable property of your text.

- The “Top Words” section visualizes repetition in real time.

- The textarea uses a monospaced font for a clean writing feel.

Conclusion

Seeing how a word counter works teaches something about how browsers read text.

When you type, the browser isn’t just painting letters. It’s capable of parsing, counting, and interpreting your content locally. Every step (segmentation, matching, filtering) mirrors how more advanced tools work: grammar checkers, translators, AI writing assistants.

If you can build a word counter, you’ve already built the foundation for:

- Readability analysis (average sentence length, grade level)

- Keyword density checks

- Tone analysis (detecting adverbs or passive voice)

- Change tracking (comparing text revisions locally)

Try It Yourself

Open the Vayce Word Counter in another tab. Type, paste, or drop in some text. Watch the stats update as you go.